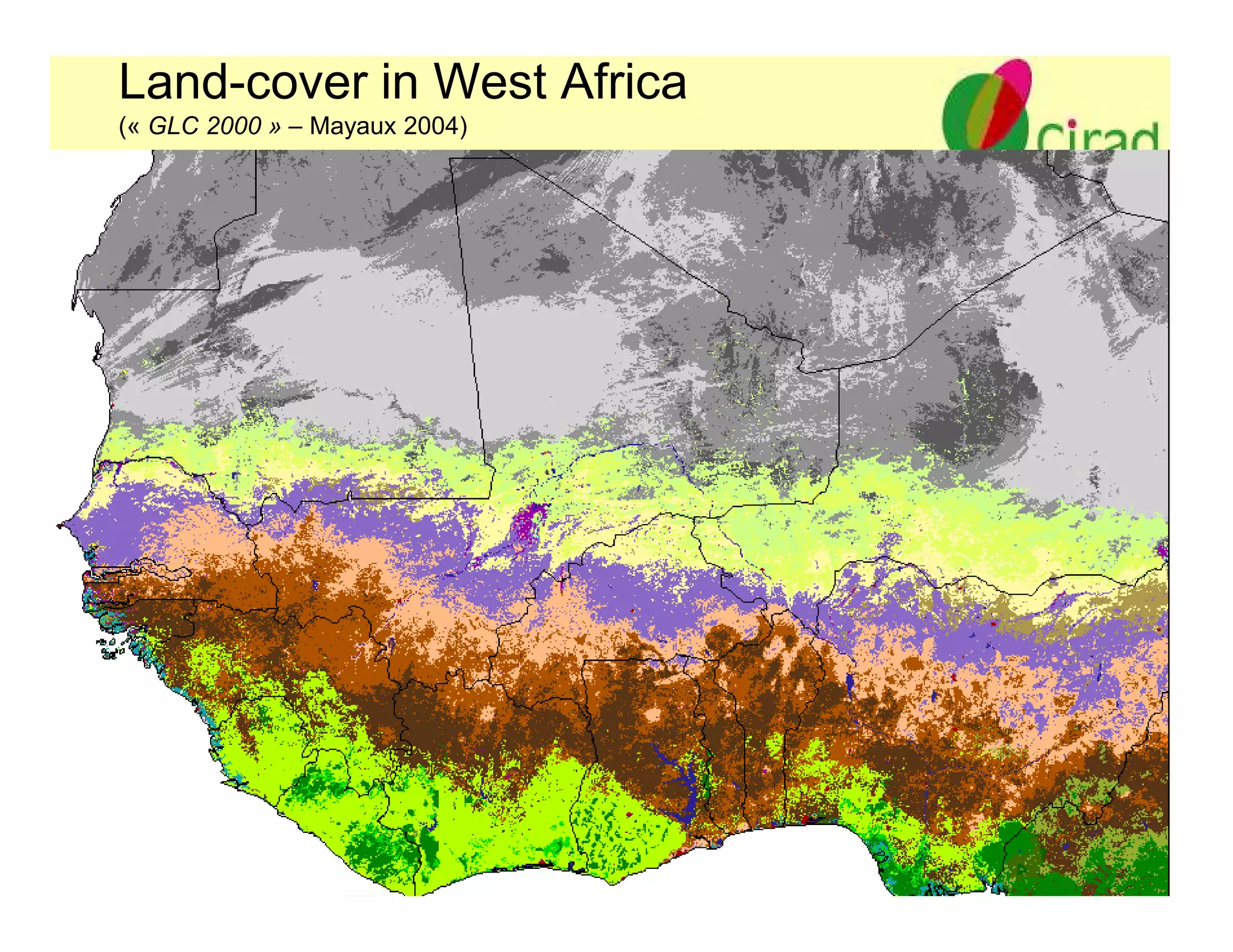

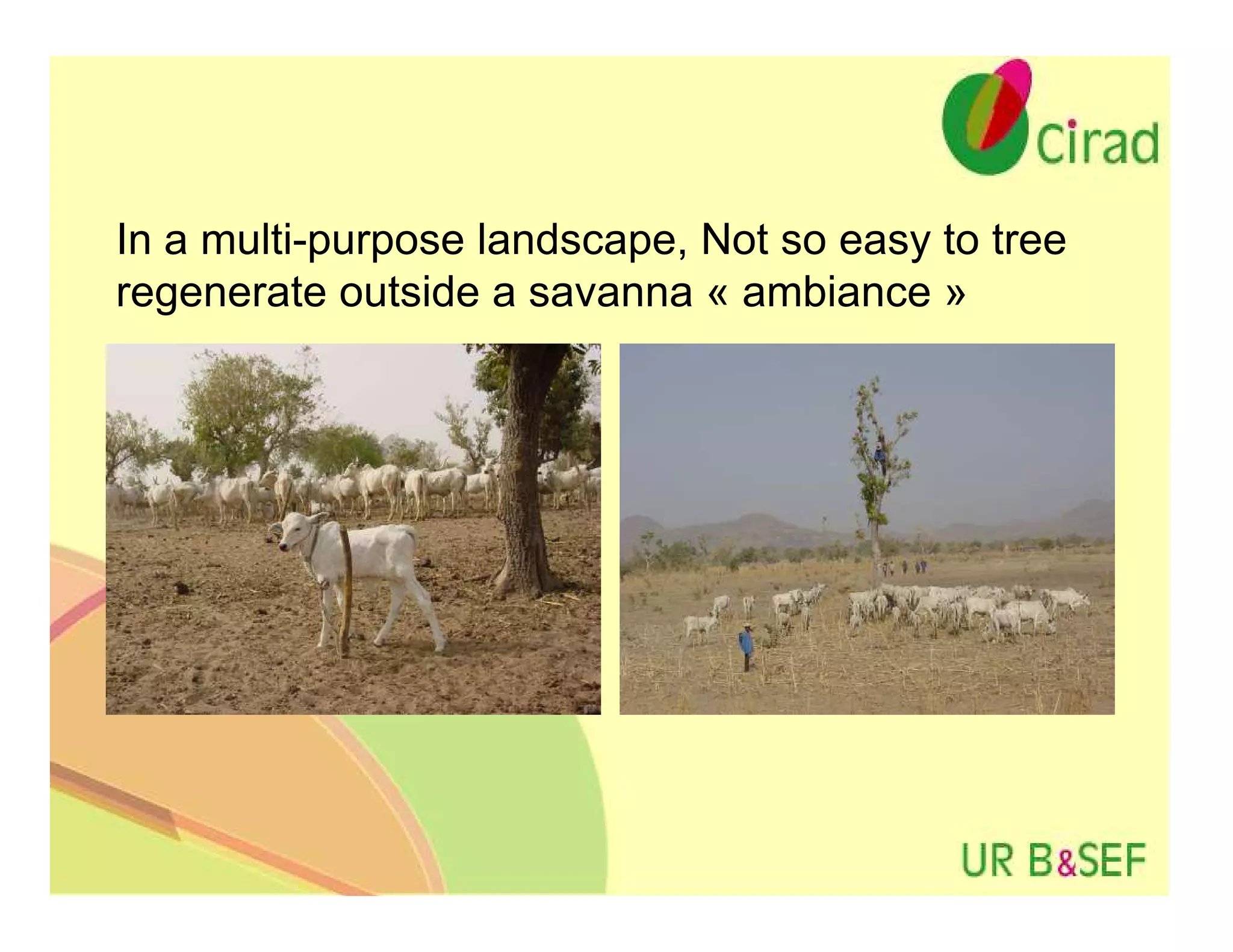

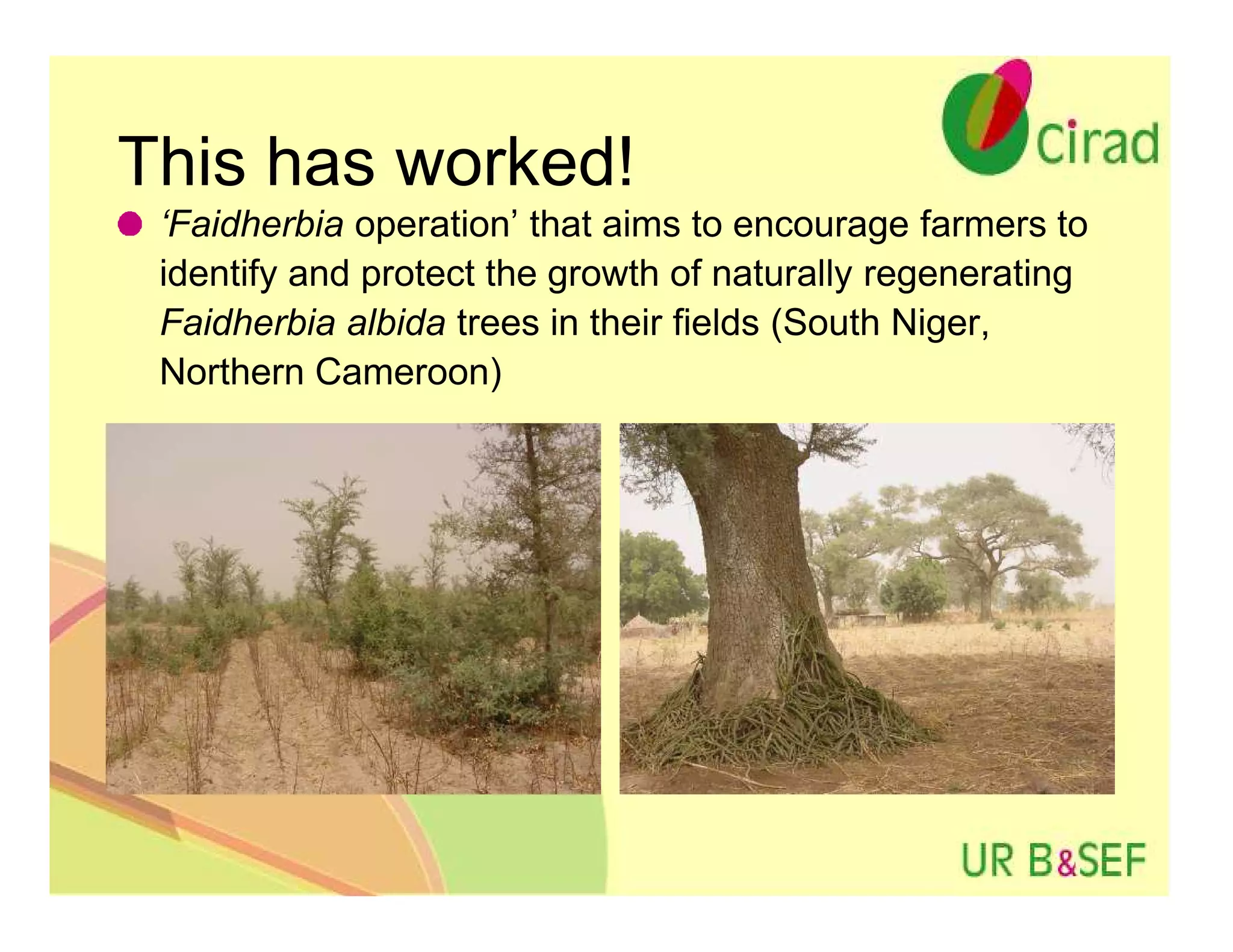

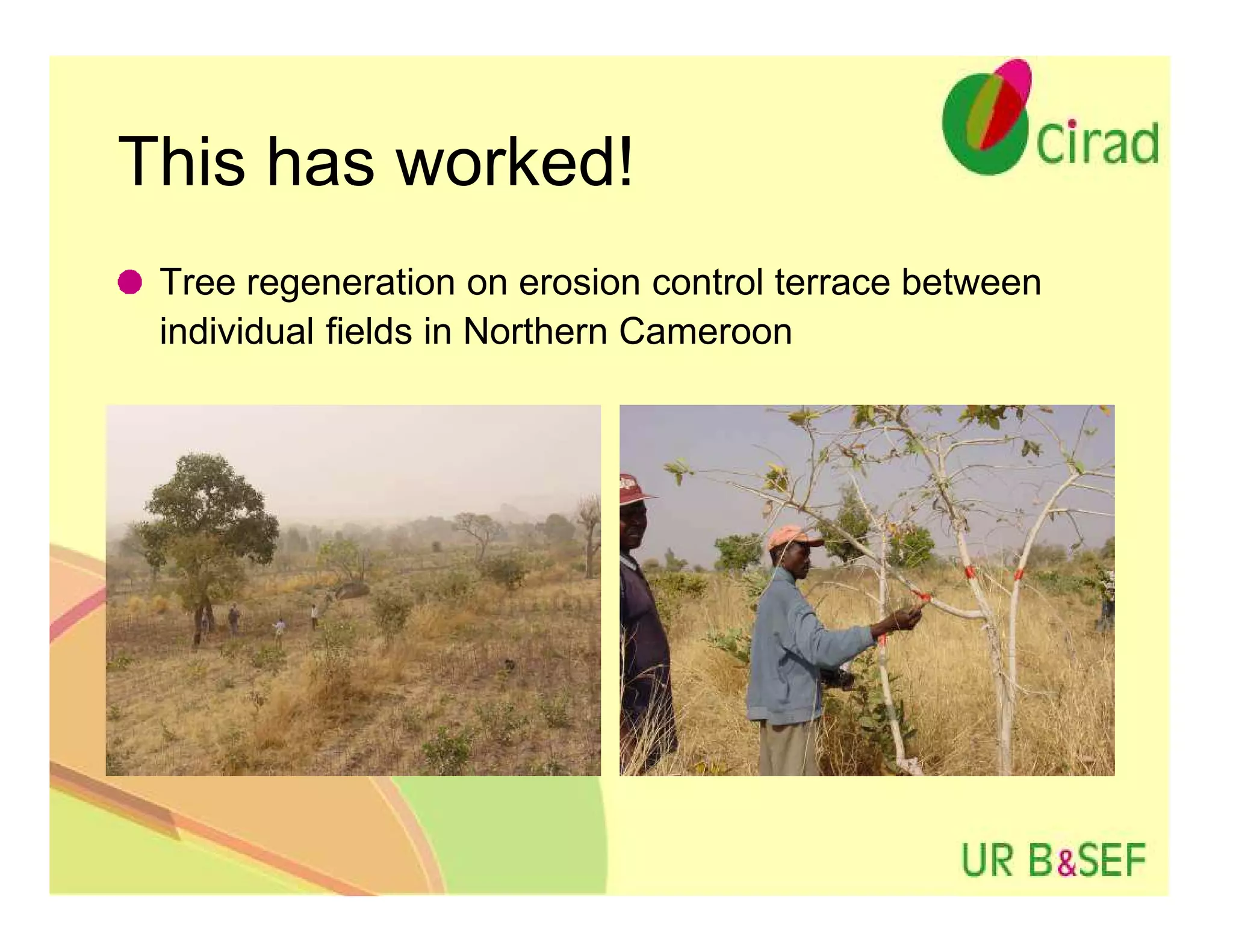

The document discusses the challenges of promoting tree regeneration in the Sahel, highlighting the complex interplay of environmental, political, and social factors that affect forestry management. Despite various reforms and community forestry initiatives over the past decades, significant progress in forest regeneration has not been achieved, with individual actions proving more effective. It raises questions about the future of community forestry, the role of privatization, and the impact of global biodiversity and carbon sequestration agendas.